Causal Inference - Behind the “why?”

Introduction

Correlation is not causation

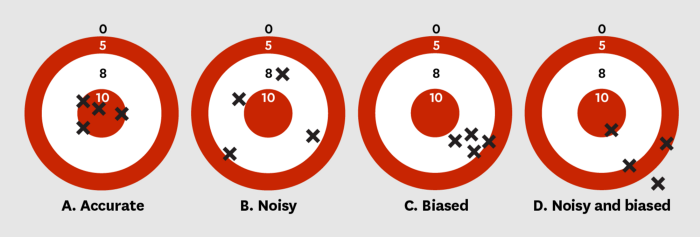

We, as statisticians and data scientists have been playing with data for so long that we have well-defined methods to identify and express correlation between variables[1] - E.g. there is a positive correlation between increased level of CO2 in the air and global warming. This means that an increase in CO2 levels is usually (depends on the degree of correlation) seen with an increase in global warming levels. However, and here is the interesting part. It does not mean that the rising CO2 levels caused global warming. Nor does it mean that rising global warming levels caused increase in the atmospheric CO2. It could mean either of those, but before we can conclusively say that we need to perform some form of analysis. This analysis should help us identify if rising CO2 levels cause global warming or the other way round. We might also find, as the result of the analysis, that some other factor, previously unaccounted for and still not uncovered (called a confounder)[2], was causing an increase in both CO2 and global temperature levels. We might also find that there is no causal relationship between CO2 and global warming. So a causality test will help us establish any of the four outcomes. Assuming A and B are two observed events:

- A causes B denoted by A -> B

- B causes A denoted by B -> A

- Some other factor is causing both A and B

- A and B have no causal relationship

Now, we need to know what kind of analysis to do so that we can infer the nature of the causal relationship. Before that, here’s another example of correlation and causation.

The 1964 smoking-lung cancer report and the backlash by statisticians

As an example of the difficulties in establishing causality, consider the relationship between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. In 1964 the United States’ Surgeon General issued a report claiming that cigarette smoking causes lung cancer. Unfortunately, according to Pearl the evidence in the report was based primarily on correlations between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. As a result the report came under attack not just by tobacco companies, but also by some of the world’s most prominent statisticians, including the great Ronald Fisher. They claimed that there could be a hidden factor – maybe some kind of genetic factor – which caused both lung cancer and people to want to smoke (i.e., nicotine craving). If that was true, then while smoking and lung cancer would be correlated, the decision to smoke or not smoke would have no impact on whether you got lung cancer.

Determining causality on the basis of correlations is tricky, at best, and can potentially lead to contradictory conclusions.

More use-cases of Causality:

- Agents simulate customer behavior - decisions like purchasing a product, clicking an ad on a website

- To understand what causes the customer to make those decisions, our association model might tell us that a purchase happens when there is a promotional activity. There are more forces at play here.

- Association models inflate the impact of promotional activity ignoring hidden variables called confounders, because there is no data available for them. One such variable that could actually be causing the customer to purchase is need for the product.

- Causal model can help understand what really causes an agent to make a decision, leading to a more accurate simulation of the customer’s behavior

How to identify a causal relationship

One way to establish causal relationships is by performing Randomized Controlled Experiments.[2]

We suppose there is some experimenter who has the power to intervene with a person, literally forcing them to either smoke (or not) according to the whim of the experimenter. The experimenter takes a large group of people, and randomly divides them into two halves. One half are forced to smoke, while the other half are forced not to smoke. By doing this the experimenter can break the relationship between smoking and any hidden factor causing both smoking and lung cancer. By comparing the cancer rates in the group who were forced to smoke to those who were forced not to smoke, it would then be possible to determine whether or not there is truly a causal connection between smoking and lung cancer. But we cannot do that.

Hence it’s not always possible or practical to perform such RCEs because of moral, legal or logical reasons.

Confounding and the missing data problem

Why is estimating a causal effect difficult? To put it simply, the fundamental problem is that we can never actually observe a causal effect. The causal effect is defined to be the difference between the outcome when the treatment was applied and the outcome when it was not. This difference is a fundamentally unobservable quantity. For any individual, we can only ever observe their blood pressure either in the situation (1) when they take the drug or (2) when they don’t. We can never observe both since an individual cannot simultaneously both take the drug and not take the drug. This is a very unique type of missing data problem.[4]

A randomized controlled experiment suffers from the issue of confounding - These variables that differ between the treatment and control groups are called confounders if they also influence the outcome.[4]

We will briefly touch upon 4 frameworks related to Causal Inference:

-

Judea Pearl and Causal Calculus

Judea Pearl came up with a solution: One can derive causal relationships solely based on observed data - you don’t have to perform RCEs. For that purpose, he developed Causal calculus a.k.a. do-calculus.[5][6][7][8][9][10] Start reading about it with this[11]

Causal Calculus is based on Bayesian Networks[12][13], which were also developed by Pearl in 1980s.

Say we are ultimately interested in how variable y behaves given x. do-calculus differentiates between the two conditional probability distributions: observational represented by p(y|x): the distribution of Y given that I observe variable X takes value x interventional represented by p(y|do(x)): the distribution of Y if I were to set the value of X to x

-

Rubin Causal Model

Rubin defines causal inference based on the framework of potential outcomes[14][15]

Potential outcomes are expressed in the form of counterfactual conditional statements of the case conditional on a prior event occurring.[16]

To measure the causal effect of a treatment on an outcome, we would have to look at the data for the outcome on the sample in two alternate universes - where the treatment was applied, and where there was not treatment applied. This is not possible, hence, data for one of the potential outcomes is always missing

Rubin causal model implements several methods like Propensity score matching to find control samples similar to treatment samples, so that a causal effect can determined by looking at the difference of the two outcomes

-

Granger Causality

Granger Causality test is used to explain the direction of causality between time series variables.

The test represents that for two variables, say X and Y, if X is influenced by both lagged values of X and lagged values of Y, then it is called as Y Granger causes X (Y→X). Similarly if Y is influenced by its lag and the lagged values of X, then we call it X Granger causes Y(X→Y).

An event may Granger cause another event but not actually cause it. A simplistic example for this would be, in the morning just before the sun rises the rooster will crow. If you run a Granger causality test on a series of rooster crows and sun rises, you will find that the rooster’s crow causes the sun to rise. But then this can’t really be truly a causal relationship.

-

Convergent Cross Mapping

Convergent cross mapping (CCM) is also used to find causal effect between two time series variables, like the Granger causality test

However, in dynamic systems with behaviors that are at least somewhat deterministic, information about past states is carried forward through time (i.e., the system is not completely stochastic), hence Granger’s approach cannot be applied

It follows from Takens’ Theorem that if x does influence y, then the historical values of x can be recovered from variable y alone.

A simple explanation of Cross Mapping: A time delay embedding is constructed from the time series of y, and the ability to estimate the values of x from this embedding quantifies how much information about x has been encoded into y. Thus, the causal effect of x on y is determined by how well y cross maps x.

Contrasting Pearl’s and Rubin’s theories of Causal Inference

These two models are not exactly opposing each other[17][18].

Rubin's work in words of Gelman[19]: “The research programme under which all causal inference problems can be framed in terms of potential outcomes”

Pearl's work in words of Gelman: “The research programme under which all causal inference problems can be framed in terms of graphs, colliders, the do operator, and the like” [20]

Pearl prefers Bayesian and graphical models

Rubin/Gelman prefer continuous, non-graphical models

Rubin's theory has had success in applied research, more so than Pearl's[21]

Pearl's work is not understood by some. But people who understand and side with Pearl's work find Rubin's work lacking. Some concepts like M-Bias cannot be express just using potential outcomes.[22]

Packages for causal inference

- DoWhy - A Python library for causal inference that supports explicit modeling and testing of causal assumptions.

https://github.com/py-why/dowhy

Docs

DoWhy builds on two of the most powerful frameworks for causal inference: graphical models (Judea Pearl) and potential outcomes (Neyman-Rubin). It uses graph-based criteria and do-calculus for modeling assumptions and identifying a non-parametric causal effect. For estimation, it switches to methods based primarily on potential outcomes.

- CausalML - A Python Package for Uplift Modeling and Causal Inference with ML

https://github.com/uber/causalml

Docs

It provides a standard interface that allows user to estimate the Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE), also known as Individual Treatment Effect (ITE), from experimental or observational data. Essentially, it estimates the causal impact of intervention W on outcome Y for users with observed features X, without strong assumptions on the model form.

- CausalNex - A Python library that helps data scientists to infer causation rather than observing correlation.

https://github.com/mckinsey/causalnex

Docs

CausalNex aims to become one of the leading libraries for causal reasoning and “what-if” analysis using Bayesian Networks. It helps to simplify the steps to learn causal structures, allow domain experts to augment the relationships, estimate the effects of potential interventions using data.

- EconML - A Python Package for ML-Based Heterogeneous Treatment Effects Estimation

https://github.com/py-why/EconML

EconML is a Python package for estimating heterogeneous treatment effects from observational data via machine learning. This package was designed and built as part of the ALICE project at Microsoft Research with the goal to combine state-of-the-art machine learning techniques with econometrics to bring automation to complex causal inference problems.

- CausalImpact - An R package for causal inference in time series. [not actively maintained since 2023]

https://github.com/google/CausalImpact

This R package implements an approach to estimating the causal effect of a designed intervention on a time series. For example, how many additional daily clicks were generated by an advertising campaign? Answering a question like this can be difficult when a randomized experiment is not available. The package aims to address this difficulty using a structural Bayesian time-series model to estimate how the response metric might have evolved after the intervention if the intervention had not occurred.

Next Steps

A comprehensive analysis of the available packages on real datasets

References:

[1] Correlation vs Causation video. https://www.coursera.org/lecture/inductive-reasoning/correlation-versus-causation-44nZu

[2] RCTs. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randomized_controlled_trial

[3] http://causalinference.gitlab.io/kdd-tutorial/

[4] Confounding. http://www.rebeccabarter.com/blog/2017-07-05-confounding/

[5] Intro to Judea Pearl’s work. https://www.quora.com/What-is-Judea-Pearls-work-on-causality-in-a-nutshell

[6] Judea Pearl’s paper about do-calculus: https://projecteuclid.org/download/pdfview_1/euclid.ssu/1255440554

[7] A beginner’s intro to Pearl’s paper: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1305.5506.pdf

[8] Intro to do-calculus. https://www.inference.vc/untitled/

[9] Series of blog posts: https://formalisedthinking.wordpress.com/tag/causal-calculus/

[10] Slides for do-calculus. Concise: https://www.cs.ubc.ca/labs/lci/mlrg/slides/doCalc.pdf

[11] http://www.michaelnielsen.org/ddi/if-correlation-doesnt-imply-causation-then-what-does/

[12] https://www.probabilisticworld.com/bayesian-belief-networks-part-1/

[13] https://www.probabilisticworld.com/bayesian-belief-networks-part-2/

[14] https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/178159/is-there-an-intuitive-way-to-understand-the-rubin-causal-model-and-the-potential

[15] Rubin Causal Model video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LrmrH26EhSo

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubin_causal_model

[17] https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/45999/introduction-to-causal-analysis/298744#298744

[18] https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/249767/which-theories-of-causality-should-i-know

[19] Andrew Gelman - Rubin’s student http://www.nber.org/papers/w19614.pdf

[20] Slides contrasting Pearl’s vs Rubin’s model http://leedokyun.com/obs.pdf

[21] https://andrewgelman.com/2009/07/05/disputes_about/

[22] https://stats.stackexchange.com/a/299090/220323

[23] Documentation for DoWhy https://causalinference.gitlab.io/dowhy/

[24] DoWhy language. https://github.com/Microsoft/dowhy#a-unifying-language-for-causal-inference

[25] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/dowhy-a-library-for-causal-inference/

[26] Amit Sharma DoWhy video https://mediasite.kellogg.northwestern.edu/Mediasite/Play/8e78dc83c6fb4d20abeeb18028a8f7071d?catalog=1533bdef-0c88-4513-ad97-5fce50c92e62

[27] Causal Effect package https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/causaleffect/vignettes/causaleffect.pdf

[28] Daggity http://dagitty.net/primer/