Oftentimes while discussing the results of a statistical analysis, be it sampling instances from a population or making a supervised machine learning model for making predictions, we come across the word ‘noise’. Noise in the data is something that cannot be modeled. It is assumed to be random and is kept in an equation as a perfunctory variable, just so that we are mathematically correct. The equation is then further used to convey the result we wish to, and the noise element, which was previously there for completeness, now completely disappears in the name of brevity.

Despite being given little importance in the mathematical equations while modeling real-world phenomena, noise is actually an important aspect in the real world.

The following ideas are expanded from the discussion of Daniel Kahneman on the podcast Hidden Brain, where he talks about how noise affects our judgement, and impacts our lives.

What is noise

Noise is randomness. It is the variability observed in individual but similar events.

When two doctors see a radiography report, they might come to different conclusions. When two underwriters assess the risk in a situation, they might come up with vastly different insurance premium quotes.

Extraneous factors like weather, sometimes create noise. University admissions staff tend to give academic performance more weight-age than extracurricular activities on rainy and cloudy days than on sunny days. The weather also seems to heavily influence the sentences given out by judges in criminal courts. Harsher sentences are given out on cloudy days and judgements made on sunny days with clear skies lead to less extreme sentences.

Doctors are more likely to prescribe medicines to psychiatric patients who want them, later in the day than in the mornings. This might be due to the fact that doctors are drained of energy towards the end of the day and do not resist a patient who wants a medicine. Scary stuff.

These are cases where we would want to see the same result, no matter the medical professional, judge, insurance underwriter, or the color of the sky that day.

Noise is not always bad

Noise is not always bad though. Wherever there is a selection mechanism, noise is preferred and it will produce varied options to select from. In creative enterprises where idea generation and innovation is needed, noise creates variance that is desirable. The evolution of species benefit from noise too.

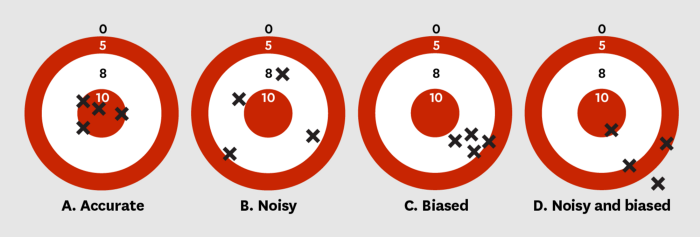

Noise is not bias

One of the main insights for people familiar with statistics and machine learning is to understand the difference between noise and bias.

Algorithmic bias is actively being discussed these days where algorithms produce results that are biased in a particular way — like against a race of people. While looking at a particular case of algorithmic bias, it is easy to understand why a faulty algorithm produced a biased result. A machine learning model trained on historical data would reflect historical patterns. If a certain race of people has been receiving harsher criminal sentences in courts historically, then it is understandable that a model trained on this data would exhibit a similar bias. This bias is not random, is visible at an individual level and also at an aggregate level. But this is not true for noise.

Noise is detected at aggregate level. It is also reduced by taking averages

Noise is not observed in individual cases, but only in aggregates. This is particularly hard for us to understand as we tend to think more in stories than in statistics.

When we take multiple, independent judgements/estimates and take an average of them, we get closer to the truth. This is called wisdom of the crowd. Independent is a key word here, as people giving estimates should not be biased by estimates given by others.

Interestingly, wisdom of crowds can also be seen with only one person. When a person estimates a quantity, say the number of schools in their city, multiple times over a period of time, then the average of all these estimates would be closer to the true value.

When people are asked to give an answer to the question a second time, this time being told to think about the question differently that they did the first time, the average of the two answers is better than both answers.

This is not true for bias. Taking multiple biased judgements and averaging them, makes the bias even more stark in the result. This is because bias is not random.

Algorithms make mistakes and are punished severely for them

Algorithms by nature have less noise because they are trained for exactly that. They may still have bias.

Even if we eliminate bias, algorithms can still make mistakes, much like humans. However, we are critical of an algorithm once we know that it has made a mistake; we would not trust it. If a self-driving car causes a road accident vs a human driver, we tend to be more comfortable with the human driver’s mistake than the self-driving car’s. It is not enough for an algorithm to be 100 times more accurate than a human on a task, it has to be almost 100% accurate for it to be trusted by humans.